TWO WAYS TO READ THE STORY

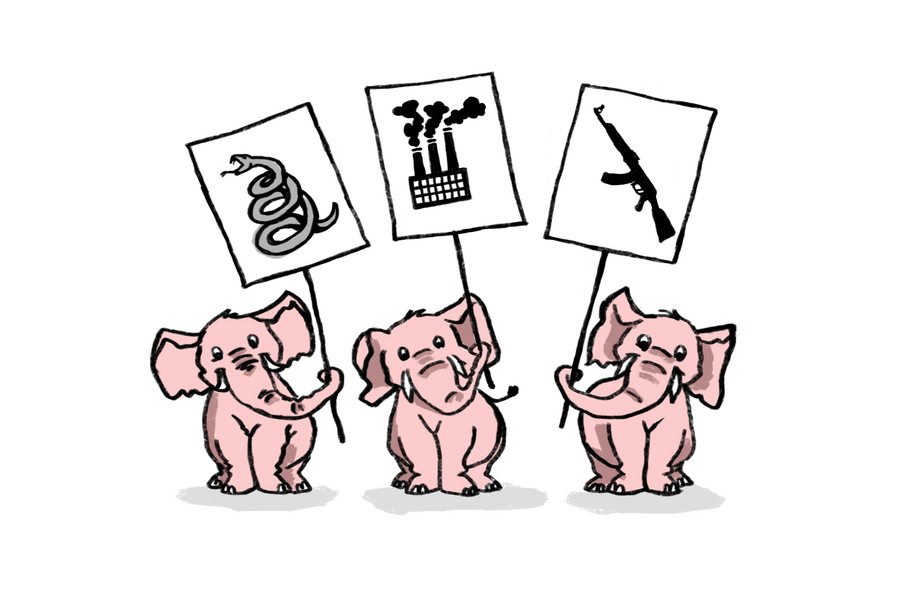

Emily Collins, a rising junior at Texas Christian University and an executive board member of the TCU College Republicans, cares deeply about many typical conservative issues: limited government, border enforcement, Second Amendment rights, low taxes, increased military spending.

Another topic she’s passionate about: climate change.

“We’re having some sort of negative impact on the environment, and I believe it’s our responsibility to alleviate any negative impacts we’re having, and to be proactive while we can rather than reactive when it’s too late,” says Ms. Collins, a Spanish major who is spending the summer working for Students for Carbon Dividends (S4CD), a coalition that includes 23 college Republican groups along with a handful of campus Democratic and environmental groups. “I think that younger people care about it more, because we are seeing the effects it’s having.

“It’s more of a pressing issue for us,” she continues, “We see it as an opportunity to take action and make sure the Earth can be safe for generations to come.”

While climate change remains a starkly partisan topic, some polls show an emerging generation gap when it comes to how younger Republicans view the issue. They’re more likely to accept the scientific consensus around climate change and more likely to push for clean energy development. And groups like S4CD and Young Conservatives for Energy Reform are working within that gap to build a grassroots coalition that allows young voters to advocate for climate action without leaving behind their conservative principles.

“Young people are more likely to have studied climate science in school, and to have a high regard for science,” says Alexander Posner, a rising senior at Yale University and president of S4CD. “As young people with generations ahead we have the most to gain or lose from the issue.” Posner adds that he sees a natural role for college campuses and the younger generation to take the lead on bridging the partisan divide.

“Student movements historically have often laid claim to the counterculture,” he says. “The dominant culture today is tribalism and bitter partisanship. By working together … we’re hoping to reorient the tone and tenor of our politics.”

An emerging shift

In a Pew Research Center poll released in May, 36 percent of Millennial Republicans (those born between 1981 and 1996) said they believe the Earth is warming mostly due to human activity – double the number of baby boomers in the GOP who say the same. Millennial Republicans are also more likely than baby boomers to say they are seeing effects of climate change where they live and that the federal government isn’t doing enough to protect the environment. They’re less likely than their elders to support expansions of fossil fuel energy sources like coal mining, fracking, and offshore drilling.

That’s not to say a big partisan divide doesn’t still exist: Young Republicans may be twice as likely as older conservatives to believe human activity is causing the Earth to warm, but the number pales in comparison to Democrats across all generations, where 75 percent hold that belief (and where few generational differences exist). And across generations, Republicans in the poll tended to be in agreement that policies aimed at reducing the effect of climate change either made no difference for the environment or did more harm than good.

That hesitation about climate policies among conservatives is some of what Mr. Posner was hoping to address when he launched S4CD earlier this year. When he talks to other conservatives, he emphasizes mitigation strategies that are underpinned by free-market principles, such as carbon pricing and dividends schemes. He also tries to allow for a range of beliefs on climate science – where even climate-change skeptics might support it as a sort of “insurance policy based around the free market.”

Michele Combs, the chairman and founder of Young Conservatives for Energy Reform (YC4ER), also says she focuses conversations on natural points of agreement – and often avoids mentioning climate change at all, while working to promote renewable, clean energy across the United States, often at the state level.

“Climate change is not a litmus test for us,” she says. “I say this is a marathon, not a sprint, and how we get there isn’t important. We use different avenues to get to the end result.”

Ms. Combs originally came to the topic when she learned about health dangers from coal-fired power plants while pregnant with her first child. “I was a conservative, pro-family Republican all my life, and I thought, ‘I can’t believe we’re not involved in this.’ ”

Young Republicans, she says, get the issue: They grew up with science education, they grew up recycling, and they aren’t as hampered by entrenched views. A poll that YC4ER commissioned more than a year ago of young conservative voters found overwhelming support for renewable energy, and a clear majority who accept that the climate is changing due to human activity.

Finding the ‘right messengers’

Part of the problem with gaining traction among policymakers and voters, Combs says, has been having liberals always being the ones advocating pushing the issue, making it more partisan than it needs to be.

The issue “needs the right messengers,” says Combs.

Could the younger generation really be the leading edge of a movement to shift thinking on climate policy more broadly within the GOP, the way, say, that generational shifts in opinion helped change the policy landscape on gay marriage?

Some experts are skeptical, pointing to the deep rifts that still exist.

“Either it’s a real cohort effect, and you’re seeing one generation that’s more liberal on the issue, or it’s just a phase, and it will pass as these voters age and become more conservative,” says Dan Kahan, a Yale professor of law and psychology who studies the roots of partisanship.

What Professor Kahan sees as more critical is understanding how some conversations can be productive while others turn people away. Asking “whose side are you on?” instantly causes people to hunker into opposing camps, while focusing instead on solutions, and how we can continue to live the way we want to live, can lead to progress. He sees the biggest source of a potential push for climate action to be people – like those in southeast Florida – with a vested economic stake in the issue.

Similarly, Edward Maibach, director of George Mason University’s Center for Climate Change Communication, says that while he’s somewhat encouraged by the polls showing that conservative Millennials are more concerned about climate change than their parents’ or grandparents’ generation, he’s more encouraged that polls are showing an increase in moderate Republicans’ concern about the issue in the past year.

“I suspect this trend will continue, given that climate impacts in the United States are becoming more obvious all the time, and perhaps this trend will be led by conservative Millennials and Gen-Xers,” says Professor Maibach in an email.